A recent report by the National Assessment of Educational Progress described 4th and 8th grade student reading and math test scores as showing “modest improvement” in 2007, but “stalled improvement” in 2009.

The lack of student improvement is cause for alarm and of course all eyes are directed at teachers, but there are other concerns that need to be addressed when considering 4th and 8th grade test scores. Factors that could be affecting the test scores and not mentioned in the article is that in most classrooms, teachers must teach to three and sometimes four different cognitive developmental levels at one time. The cognitive developmental levels are connected not so much to intelligence or motivation but simply to maturity or age. In other words, one can’t expect all four year olds to be able to ride two-wheelers because they are at different developmental levels. That is, a small percentage of four year olds will have no problem riding a two wheeler; a much larger percentage, with some practice, will succeed; another percentage will not only have a longer learning period, but probably will also need training wheels or scooters to scaffold riding a two wheeler or wait until their gross motor skills catch up. Children who need more time to catch up or practice should not be looked at as failures. They are simply not ready to use their bodies to ride two wheelers no matter how great a teacher or parent’s teaching ability.

The same example might be used to measure classroom performance or the reading and math test scores of 4th and 8th graders. Teachers use many techniques and strategies to reach all their students. The problem is that there is only so much time in the school day to teach. Mandated curriculums, shortened school years, the presence of electronic devices, disorganized home environments, and other distractions are factors that must be recognized as having a significant effect not only on overall learning, but also on test scores.

For example, 4th graders or eight and nine year olds experience the dilemma of being locked into a curriculum with a stage of cognitive development in spite of the fact that many students can entertain only two ideas at a time — in math it could be multiplication and regrouping. However, if one visits any 4th grade classroom he will notice students are being asked to learn long division which is an abstract thinking exercise requiring the ability to entertain three plus ideas including math facts. An examination of the students’ math test questions would reveal that a proportion of the test questions are geared toward abstract thinking, which for almost 85% of 4th graders is similar to asking them to ride two wheelers. It is developmentally challenging and difficult for this age group to work at this level without many hours of practice or remediation. Reading can be just as challenging because many of the test questions require students to read long passages and then answer abstract questions which force students to think out of the box or entertain more than two ideas at a time.

For 8th readers you would assume the test questions would be an easier task but this is not the case. One study showed that only 30 percent of high school seniors think abstractly. What does this say for 13 and 14 year olds?

There is nothing wrong with exposing students to higher order thinking. But if the child is not developmentally ready then an educator must return to the 4-year old’s dilemma of riding a two-wheeler. Again, with much practice and even training wheels most children will eventually “catch up.” Again, apply this example to an aggregate of 4th and 8th reading and math national test scores and the scores can be misleading. One year a teacher may have a group of 4th graders who are developmentally more mature and the next year another group in which the developmental levels are lower or immature. Could that factor change test scores from “modest” to “stalled?”

With this in mind we must ask the question why some schools score higher than others regardless that teachers use the same curriculum and techniques even when the demographics (socio-economic, parent educational levels, and language to name but a few) are the same. In my opinion, the answer is also the problem? Maybe the reason why school test scores are different regardless of similar demographics and even developmental stages is due to a lack of student practice or motivation to master reading and math skills? Ask most any four year old what is it like to learn how to ride a two-wheeler without practice or training wheels and their body language will probably say, “it’s really hard . . . you got to practice a lot!”

Therefore, to base test scores on student developmental levels might seem overly simplistic but if this article makes parents realize that reading and math skills require hours of practice, then (perhaps) I have achieved my goal.

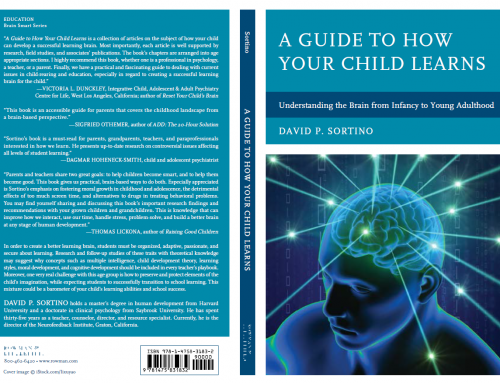

*Dr. David Sortino is a psychologist and currently Director of Educational Strategies, a private consulting company catering to teachers, parents, students. Dr. Sortino can be reached at davidsortino@comcast.net or 707-829-8315,